| kezdőlap | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | hátsó borító |

The Heritage of Generations

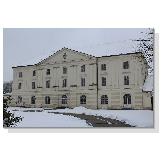

Körmendby Dr Zoltán Nagy A Guide to the Permanent Exhibition at the Rába Local History Museum The author is most grateful to Lajos Balogh, on whose text he drew freely in presenting the scientific section of the exhibition. Photographs: László Dallos Viktória Vizi Károly Péter Szendi László Tóth Publication of this booklet was subsidized by the Museum Council of the National Cultural Foundation. Design: Ernő Csaba Kiss Cover design: Tamás Jámbori Published by the Rába Local History Museum, Körmend Publisher responsible: Dr Zoltán Nagy, Curator Cover picture: The main building of the Batthyány Mansion, Körmend Back cover: Part of a family tree of the Batthyány family, hand-painted in the 18th century The Rába Local History Museum (named after the river that runs through Körmend) occupies the first floor of the west wing of the Batthyány Mansion, once the seat of a great aristocratic family. The permanent exhibition was mounted in 1994 to mark the 750th anniversary of the granting of the town’s charter. It presents the district’s natural endowments, important archaeological and cultural finds, articles and documents linked with the history of the old market town, and a large collection of relics of its bygone craft industry, gilds and associations. The first room contains the scientific section of the exhibition. The first display case, inscribed ‘A window to the past-what the Rába reveals’, contains fossilized remains of plants and animals from the Pleistocene, found in the Rába’s gravel bed. The Rába is the most important river in Transdanubia (the part of Hungary that lies west of the River Danube). Along with petrified remains of an oak trunk and the impression of an indigenous primitive pine, there is a petrified mammoth’s tooth, the jawbone of a three-toed primitive horse, and the molar of a woolly rhinoceros. The last, familiar from cave paintings, roamed the area in the glacial period several hundred thousand years ago. Life in the waters and along the banks still presents a varied picture today. The Rába is a wild river, with a rapid flow and successive bends. These are sometimes shorn off when the banks break, giving rise to backwaters. Where the torrent meets an obstacle, whirlpools develop. The Rába supports a remarkable variety of life. Characteristically, the banks are lined with gallery woodland of willow, home to the attractive marsh marigold or kingcup (Caltha palustris). Yellow water lilies (Nuphar lutea) makes an enchanting sight bobbing on the water. The greater bladderwort (Utricularia vulgaris) is an insectivore found among the weed of the backwaters, a danger to small crayfish and young fry as well. The typical creatures of the marshes include tortoises, spotted and crested newts, and grass snakes, which feed on small fish and frogs but are harmless to man. Thick-furred muskrats and sleek mallard duck (Anas platyrhynchos) are among the creatures that live and feed in the water. The nests found include those of the great reed warbler (Acrocephalus arundinaceus), an artistic builder in the reeds, the bittern (Botaurus stellaris), a master of camouflage, the little ringed plover (Charadrius dubius), which seeks insects along sand and gravel shores, and the penduline tit (Remiz pendulinus). Anglers are interested to see some of the Rába fish. The display includes a loach no longer found there (Noemachilus barbatulus) and the increasingly rare wels (Silurus glanis), as well as the mirror carp (Cyprinus carpio specularis) and the pike (Esox lucius), which can grow to a vast size. Centuries ago, it was not unusual to catch great white sturgeon (Huso) in these waters for fast days. Commoner fish were caught by the cartload to supply the table of the lords of nearby Németújvár (Güssing). Using a harpoon to catch fish was banned at the end of the last century, but such skills linger to this day. Rába fish are displayed here in a 150-litre aquarium, to give a closer view of nature. Evidence of great catches in the past survives in yellowing photographs: a 15-kg mirror carp caught by Béla Belencsák in 1954, and a 50-kg wels hooked by Sándor Bejczi and recorded for posterity before it went into the pot in 1935. The meadows, especially the lush water meadows rich in herbaceous plants, are notable for their colourful wild flowers and varied insect life. One protected plant found among the riverbank alders is the globeflower (Trollius europaeus), a relict from the glacial period. Other notable flowers include Siberian irises (Iris sibirica) in early summer and marsh gentians (Gentiana pneumonanthe) later in the season. Snakeshead lilies (Fritillaria meleagris) once flowered profusely on the Rába water meadows in the early spring, but today they form a protected, endangered species. So does the green-winged orchid (Orchis morio). The lovely, but highly poisonous autumn crocus (Colchicum autumnale), found in damp meadows, has tepals that vary from pale pink to lilac or purple. The bare flowers appear in the autumn. Among the delicacies of the pastures, meadows and woodland fringes are parasol mushrooms (Lepiota procera). Common frogs (Rana temporaria) are frequent on peat moss, as are praying mantises (Mantis religiosa) in grass. Smooth snakes (Coronella austriaca) and slow worms (Anguis fragilis) are quite common as well. Wood pigeons (Columba palumbus) like to nest in gallery woodland. The magpie (Pica pica) and the nest-parasite cuckoo (Cuculus canorus) are often present in the district. So is the kestrel (Falco tinnunculus), hovering motionlessly in the air as it seeks its prey. The plants and animals of the woodlands round Körmend are equally varied. Snowdrops, heralds of spring, are widespread. Spring snowflakes (protected nationally since 1989) are found undisturbed in groves of hornbeam and oak, forming a carpet interspersed with blue Alpine squills (Scilla bifolia). The leaf-mould that clothes the woods of Turkey and common oak and hornbeam is pierced by a local rarity, Helleborus dumetorum. Also protected is the primrose (Primula vulgaris), which appears in clearings. A feature of the later summer is the scented woodland cyclamen or sowbread (Cyclamen purpurascens). The goatsbeard spiraea (Aruncus dioicus) prefers damp valleys in beech woods. Typical woodland birds include the lesser spotted woodpecker (Dendrocopos minor) and the green woodpecker (Picus viridis). The sparrow hawk (Accipiter nisus) is an agile and intrepid hunter, a scourge of smaller birds. The long-eared owl catches its prey at night and is rarely seen by day. One well-known finch in these woodlands is the hawfinch (Coccothraustes coccothraustes), whose heavy bill can tackle the hardest of seeds. Swallows (Hirundo rustica) hunt for insects by day and nightjars (Caprimulgus europaeus) at night. The nightjar’s gaping beak gave rise to a popular belief that it stole into the shed at night to drink milk from goats’ teats. There are countless fungi in the woods, among the most poisonous being the panther (Amanita pantherina) and the fly agaric (Amanita muscaria). Common fungi in the pinewoods include the cèpe (Boletus edulis) and the saffron milk-cap (Lactarius deliciosus). Of the larger woodland animals, roe deer and wild boar are frequently shot for game. One rarity is the black stork (Ciconia nigra), which nests in the district. The specimen displayed in the museum a reminder that Körmend has been called the ‘town of storks’. The daggers, traps and snares shown exemplify the inventive ways in which large and small animals were caught. One weapon used before the hunting gun arrived was the sling. Using lime twigs, snares and horsehair loops effectively, or even setting a mousetrap, required an intimate knowledge of animal habits. Songbirds that were caught were often prized highly and kept in cages made up to look like a human dwelling. Mention should also be made of the naturalists of the district. Carolus Clusius (1526-1609) was a Netherlandish physician and botanist who did important research into plant life, during a long period spent on Boldizsár Batthyány’s estates at Németújvár. He was the first to describe several plants, including the yellow day-lily (Hemerocallis lilio-asphodelus), which he found in the woods by the Rába. His assistant on several trips through Western Pannonia was (the Hungarian) István Beythe (1532-1612), a botanist, preacher and religious writer, who helped Clusius compile the Stirpium nomenclator pannonicus, a dictionary of Hungarian plants. Furthermore, Clusius left the earliest description of the flora of Western Transdanubia and neighbouring districts, in a work that appeared in 1601 and includes fungi, too. Among the later followers of the same path was István Vörös (1894-1963), a butterfly researcher and teacher from Egyházasrádóc. Vörös also collected in the Körmend district and left his collection of 3500 butterflies and insects to the Savaria Museum in Szombathely. A small selection is seen here. Ernő Horváth (1929-1990), a museum specialist, concentrated mainly on plant fossils, but also made valuable contributions to the study of plant life, to nature protection and to history. He was associated with the natural-history exhibition at Körmend in the 1960s and with the erection of a memorial to Clusius in the castle gardens. Two other famous naturalists from the Körmend district shared a passion for birds and for intensive research. József Csaba (1903-1983) was a district notary born at Nagycsákány (Csákánydoroszló), who became an authority on ethnography, linguistics and ornithology, publishing over 200 papers on these subjects in his lifetime, most of them concerning the Rába Valley. The display includes pieces from his superb ethnographic collection, which he presented to the museum in 1953. Two mangle boards come from him. One, dated 1825, shows a double-headed eagle, a lion bearing a sword, a stork and a wood pigeon. The other, a token of love given to Éva Gyurko in 1835, carries a spreading tree of life, decorated in red sealing wax. Another curiosity is a walking stick with a snake, carved in relief, on which the Hungarian coat of arms can be seen above the Lamb of God, with depictions of a monstrance and a chalice beside it. One of the finest ethnographic items in the museum is a razor case with red and green sealing-wax decoration. This was made by Pál Szalai in Szombathely in 1868, for Mihály Német. Among countless other treasures from the Csaba collection are wooden skates, a pressed carnation from the Carpathians, a flint and steel, wooden doves carved in the First World War, a wedding shawl, painted Easter eggs, a deer’s-head walking stick, a worn hunting bag, and a fist-sized sacrificial stone to which a wisp of hair belonged. The other noted ornithologist was Lajos Molnár (1853-1942), also a district notary. He was born in Körmend but lived in Molnaszecsőd. Remembered as a superlative birdwatcher specializing in Hungarian birds, he also became a master of preparing and stuffing birds. His home, which he used as a museum, was famous by the turn of the century for a collection of birds spanning all five continents. Seen here is a small proportion of this collection, which is professionally displayed and preserved at the János Olcsai-Kiss Primary School. Eleven colibri, birds of paradise, a huge macaw and a colourful toucan provide a sample of birds from New Guinea, Australia, Paraguay, Colombia, Ecuador, the Moluccas and Brazil. A lavishly produced book was published locally not long ago, presenting the work of Lajos Molnár and his matchless collection of mounted birds. Visitors entering the second room find a collection of manmade objects dating from centuries and millennia ago. Archaeological exploration, begun in the second half of the 19th century, caused intact prehistoric tools from the Körmend district to be gathered into private and society collections, and later into the museums. Rescue excavations and surface observations in recent decades have confirmed that there were several Neolithic settlements in the district in the 4th millennium BC. Several sites have yielded relics of the linear-pottery culture of Transdanubia. Cremation graves of the late Copper Age, at the end of the 3rd millennium BC were discovered at Csákánydoroszló. The human ashes were found among pieces of the vast decorated vessel shown here. Signs of prehistoric development emerged in three places when gas mains were being laid in the castle gardens (Várkert) of Körmend in 1984. They consist of extensive middens or refuse pits, from which it has proved possible to piece together plates, pots and tankards from shards. A piece of a stone for grinding cereals was also found amid debris from burnt wattle-and-daub walls. Traces of settlement by the Romans were found over a century ago on the castle mound at Katafa, by Endre Turcsányi, Evangelical (Lutheran) minister of Körmend. After several years of probing along the course of the Amber Road, archaeologists in 1980 discovered a military fort, whose name, Arrabone, is known from ancient sources. The oblong fort is bounded on three sides by a ditch and a rampart. This was unnecessary on the fourth side because of the natural steep hillside. Within the defences, made of wood strengthened with clay filling, there were buildings with a frame of wooden beams. Fortune favoured the archaeologists, for they found inside the camp a major hoard of 18 gold coins, bearing heads of eight different emperors. Along with these coins of Nero, Vittelius, Vespasian, Titus, Domitian, Trajan, Antonius Pius, Lucius Verus and Marcus Aurelius, which are in mint condition, fragments of Samian ware were found. It has been shown that the hoard was hidden in the 160s and 170s, during the wars against the Marcomanni. The remains of a cremation grave from early Roman times (a native woman) were found in the castle gardens in Körmend. Beside the ashes, one of the prize exhibits, a little scent bottle from the Italian peninsula was found intact. The cabinet also contains reconstructed vessels from urn graves of the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, found at Egyházasrádóc. The tableau on the wall by the window presents several small, scattered finds, as a cross-section of the millennia of history. They include flaked and polished stone tools, a socketed bronze axe, and a rare measure of weight: two keftiu-the Bronze-Age antecedent of money. There is a buckle from a grave, a ring with the monogram of Christ, a clay lamp, sword and arrowheads from the period of the great migrations, fragments of medieval and modern vessels with base marks, and a short series of coins. Then there is an excavation section of an in-fill from the 19th-century market town, including countless fragments of pottery, glass, stoneware, metal waste, and rejects from the local clay-pipe factory. Körmend is first mentioned in a legal document of 1238, as Curmend, which means shallows, a fortified place, or possibly a castle in the Turkic language. There it features in a boundary dispute as a royal domain. In 1244, King Béla IV granted Körmend a town charter, with the right to hold a market and broad customs concessions. Having belonged for a time to the queen, the estate passed through the hands of several magnates, before becoming a centre of the Batthyány estates in 1604. The town has only been examined archaeologically to a small extent, during rescue excavations, although the objects recovered have great importance for local people. One item recovered is a stove tile from a royal residence of the 16th century. This rare tile covered with a green lead-enamel glaze has a square face with a depiction of Queen Elizabeth (Erzsébet), widow of King Albert of Habsburg, King Wladyslaw (Ulászló) I, and Albert’s posthumous, infant son, later King Ladislas (László). Nothing else had remained of any medieval building, apart from St Elizabeth’s Church and the foundations of the castle. During recent exploratory excavations in the old inner city, traces of the settlement in the Árpád period (up to 1301) have been found at a depth of over two metres. In one place, the defensive moat and palisade came to light, and in another, early walling and a midden belonging to the buildings. Apart from 15th-century pottery shards, a vessel with a spout and the mark of its maker has been found. So have some 15th-century stove fragments, pieces of some 17th-century Renaissance-style stove tiles bearing the Habsburg coat of arms, a bead-glass tumbler, and a fragment of rare Siegburg ware with a face on it. It is logical to add here two 17th-century halberds, thought to have been found at a depth of two-and-a-half metres, during the digging of a septic tank. However, there is a rich stock of documents from the market town. The town’s surviving records include some important writings. One is a charter of 1650, written in Hungarian, granting Körmend the privileges of a Heyduck (hajdú) community. (The Heyducks, originally mercenary soldiers of peasant stock, were settled in the early 17th-century as freemen made exempt from feudal dues in return for military service.) This charter, along with several other documents of the 17th and 18th-centuries survived in the Batthyány family archives, despite the damage done in the Second World War. The first register of the Hungarian National Museum, kept in Latin, records the gift by Prince Fülöp Batthyány of a hoard of treasure found in the gardens of his mansion at Körmend. This consisted of 14th-century vessels used for eating at the Wilhelmite, Augustinian and Franciscan houses in the town and various liturgical vessels. These were probably buried when the monasteries were abandoned about 1524. Originally, the find included over 300 coins of the reigns of Andrew II, Charles Robert of Anjou, Louis the Great and Mary, 24 gilded half-buttons, 21 small buttons, 70 silver plates for the decoration of clothing, a rock crystal with a monogram of Christ, and a silver seal. Much has been lost in the storms of history. The most interesting survivals are a silver drinking goblet, a gilded silver bowl for holding holy water, three gilded cups, a silver seal, 11 silver rings, a gilded silver reliquary in the form of a pectoral cross, and a small gilded bronze crucifix. These masterly examples of Hungarian work in precious metals can be admired in the display cabinets. Körmend became the centre of the Batthyány estates in 1716. After 1769, the documents of the princely branch of the family, stretching back over several centuries, were brought here, along with much of the family’s art collection. The important picture gallery, library, arms collection and plethora of applied-art objects fell victim to the devastation of the Second World War, when the vast archives also suffered damage. The surviving pieces can be seen here, as well as in the National Museum and the National Archives in Budapest. There is a letter from Mustafa Beg, written in gold calligraphy to Ádám Batthyány in 1637. Ferenc Batthyány made his will in 1559 on parchment. The seals and signatures of the country’s great men can be seen on the last page. The dies for minting coins are a rarity. These bear the princely coat of arms and a likeness of Károly Batthyány, made by the Viennese engraver Joseph Toda in 1768. The gilded silver harness and tackle dates from the 17th-century and arrived as the spoils of war. A book of numismatics in Latin has Ádám Batthyány’s name on the title page. The arms collected have been scattered. Even what remains here bears the marks of deliberate damage. The exhibits include a sword with an Arabic inscription, a Spanish rifle of a Balkan type, a French flintlock pistol, hunting knives and powder horns. These form just a fragment of the once vast and splendid collection. The all-powerful Batthyány family, landlords of the town and owners of its castle, traced their ancestry back to the Árpád period. Tradition has it that the estate of from which they took their name was granted to Master György in 1398. In 1500, Boldizsár was granted a coat of arms by Wladyslaw II. In 1524, Ferenc received Németújvár Castle and in 1604, the family acquired Körmend. In 1630, Ádám was made a count. In 1692, Ádám Batthyány II married Countess Eleonóra Strattmann, and it became possible for their eldest son to inherit this family’s name. General Károly Batthyány received the title of imperial prince from Maria Theresa for his part in her son’s education. The princely branch of the family held the Körmend entail, whose most famous owner was the oculist Dr László Batthyány-Strattmann, who founded a hospital and treated the patients free until his death. Körmend does not have many church relics. However, the treasured possessions of the Reformed congregation include a book of Hymns for the Burial of the Dead, published in Debrecen in 1698, pewter vessels for the Lord’s Table and a baptismal ewer made in 1784, and a gilded plate for distributing the host at Communion, dated 1791. Among other notable exhibits, there is a glass jug with a pewter lid, for communion wine, a wafer-making copper dated 1842, and a ‘forbearance glass’ showing a Cavalry scene. The technical drawing done by the town mayor and architect Andreas Leithner in 1853, using an axonometric projection, gives a clear idea of how the main square looked at that time. Andor Endre Turcsányi has left to posterity some photographs of his family taken in the 1860s. These are seen with a self-portrait, five lithographs portraying him and biographical details about this highly cultivated scholar. Space has been found for a carved piece of the base of a barrel bearing the date 1811, from the tithe cellar of the Batthyány estate. There are also some First World War weapons, ornaments and souvenirs from the war museum of János Kőszegi Bartunek. One relic of interest is a ceremonial halberd bearing the monogram of Francis Joseph and the date 1871. This belonged to the royal life guards. It was left behind near Kőszeg (in the closing months of World War II, by troops fleeing before the Red Army), about the time the Hungarian Crown was buried at Velem. After several vicissitudes it found its way into the hands of a local knife-grinder and then into the museum. The third room shows relics illustrating the history of craft industry in the market town of Körmend. The town already had eight gilds for single crafts and one mixed gild in the 17th-century. The number reached 13 individual and one mixed gild in the 18th-century and 17 individual and three mixed gilds in the 19th. Almost half the townsmen were engaged in craft industry, although a great many also earned supplementary income from farming. The largest group was the shoe and bootmakers, followed by the cloak makers and tailors, and then the weavers and the cartwrights. Apart from these, 40 or 50 other trades were practised. The display includes all the relatively few articles from Körmend’s gild period that are preserved in the Vas County museums. The pewter can of the butchers’ gild is a masterpiece, made in Sopron and dated 1726. The millers’ candlesticks, bearing the date 1823, are rare by national standards. Another item not commonly found is a document of release issued by the weavers’ gild in 1821, decorated with a painting of a flower growing in a flower pot. The green-glazed tankard of the bootmakers’ gild, bearing an angel’s head and a picture of Christ, was made in 1750. This is the first objet d’art that the Savaria Museum in Szombathely is known to have acquired from Körmend. The accession was published in the 1875 annual report of the Vas County Archaeological Society. Researchers have devoted much attention to the inscribed fragments of roof tile. One of them, found when the house at Berzsenyi utca 1 was pulled down, is dated 1818 and bears the inscription INRI with a Cross and a Tree of Jesse. The most attractive of the gild record chests is the carpenters’, decorated with intarsia. Of the smiths, a special mention is due to the Zwiefel family, for their ornate trade sign and for the unique First World War memorial erected at Vasalja in 1934, which is deservedly admired by all who see it. Another publicly acclaimed artisan was Antal Weber, the tinsmith. His trade sign of a swan, sheet-metal lions, dragon water spout and mermaid gable piece looked effective and decorative on houses in the town. The cartwright Imre Raposa made the excellent 1852 drawing of a carriage, seen from several angles and authenticated by his local gild. The tools he used for making the vehicle have also survived. The bootmakers’ green-glazed gild jug of 1854 shows a knife and last. The tools of this trade can also be seen. The Kluge family of Körmend blue-dyers originated from Saxony. Pál Kluge was born in Wiener Neustadt in 1846 and worked in Sopron as a young man before moving to Körmend. There his son, Pál Kluge Junior, was born in 1873. The son took over the business in 1900, serving as a respected president of the trades association from 1907 to 1936 and as mayor of the town from 1921 to 1927. Kluge’s workshop was forcibly nationalized (under the communist regime). All that remains are some printing blocks, of which one bears the Hungarian coat of arms. Lajos and József Tóth were honeycake makers who continued to ply their rare trade in Körmend until a few years ago. They made sweets and candles, honeycake hearts and hussars for fairs, and brewed bragget, a kind of mead. Ferenc Sándor, the clockmaker, won a prize in 1888 for a clock mechanism that struck the quarters. Trained as a maker of wrought ironwork in Graz, he designed and cast all the parts for the 52 public clocks he made in his lifetime, which brought him renown far beyond his home town. Mihály Tóth and his son Lajos were excellent watchmakers, jewellers and silver engravers. Their collection of semi-precious stones was built up during their jewellery-making. Kálmán Pőcze and his daughter Mária were celebrated bookbinders for several decades, running a small stationery shop at the same time. Their products are represented by some finely bound prayer books with bone covers and metal clasps. The most active of the voluntary societies and clubs in Körmend at the turn of the century was the fire brigade. Their band, under bandmaster Manó Pavetits, had a great many successes. The dress uniform worn on special occasions included a metal helmet with a coat of arms. The Körmend Cycle Club was founded in 1889. The Udvary brothers, seen here, rode their penny-farthings to the World Exposition in Paris. They returned by way of Turin, where they visited the aged, exiled Lajos Kossuth, Hungary’s leader in the 1848-9 War of Independence. The local printing press produced a book on their adventurous trip, which also kept alive the traditions of 1848. It went into a second edition. The club’s founding minutes and banner are among the museum’s prized possessions. The atmosphere at the turn of the century is recalled in postcards, pieces of porcelain, velvet-bound keepsake albums, and an antiquated coffee grinder. A special area of the exhibition has been laid out for the traditional Hungarian ceremonial attire (díszmagyar) of a noblewoman, bought by the Savaria Museum. It consists of a deep-purple velvet pelisse with fur trimming, a matching blouse with velvet appliqué, a similar skirt, a head-dress studded with gems, and a lace veil and apron. Finally, the famous opera singer Mária Németh, born in Körmend, and her roles are remembered in original photographs and posters. |

Lakossági kapcsolatok

központi e- mail: kormend[kukac]kormend.hu

központi telefonszám: 94/592-900

fax: 94/410-623

cím:

Körmendi Közös Önkormányzati hivatal,

9900 Körmend, Szabadság tér 7.

központi telefonszám: 94/592-900

fax: 94/410-623

cím:

Körmendi Közös Önkormányzati hivatal,

9900 Körmend, Szabadság tér 7.

Hasznos információk

Programok

2023.február 6. hétfő

| H | K | Sz | Cs | P | Sz | V |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 | ||

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

25 |

26 |

27 |

28 |

Legfrissebb

- Kellemes Húsvéti Ünnepeket Kívánunk!

- Színházi előadás

- Kiállítás megnyitó

- Rendörségi hírek

- II. Országos Középiskolai Rendészeti Csapatverseny

- Változik a Körmendi Közös Önkormányzati Hivatal ügyfélfogadása

- Autó motortere égett Körmenden

- Rendőrségi hírek

- ETCS vonatbefolyásoló rendszert épít ki a GYSEV

- XIV. Tavasz ünnep

- Rendőrségi hírek

- Kóbor kutya keresi gazdáját

- Rendőrségi hírek

- Lezárt akta

- Forgalomkorlátozás Szombathelyen

- A Lasko ment tovább

- Rendőrségi hírek

- Hóátfúvás nehezíti a közlekedést továbbra is Vas megyében

- Pályázati felhívás

- Utinform jelentés

- Gysev közlemény

- Savaria Filmszínház műsora